Montana

In the summer of 2018, I took part in a National Science Foundation funded research program, songed Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). As part of this program, I spent 12 weeks at the Montana State University working under Robert Maher, a professor of Signal Processing and Audio Engineering.

Part of my research experience was to come up with my own research problem. I spent the first two weeks self-studying signal processing through Rob’s exploratory-based assignments, including going out with an audio recorder and “exploring sounds”. In that time, I took and analyzed audio recordings from different parks and natural environments in Montana- including at a nearby goat farm. That inspired me to pursue the project that I did: creating a tool for ornithologists to automatisongy detect and distinguish bird songs in long audio files. From my research, I learned that it is common for ornithologists to place an audio recorder in a place that they are interested in studying the bird population of for hours or days at a time, and then manually listen and count the number of birds they hear. This is a problem space that I think that computer technology could save a lot of time and redirect the users’ attention to analysis and exploring more complex ideas.

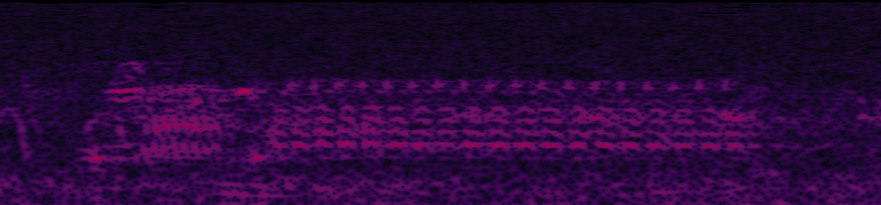

This project was a very exploratory experience for me; I learned not only about signal processing for the first time through this project, but about audio engineering detection. After reading about the latter two subjects online, I decided to constrain my problem space to detecting red-winged black birds in audio files, due to the fact that they have a very distinct song. Below, I’ve included a clip of their song, as well as the spectrogram displaying the song.

Here, I encountered a realization which I’m currently re-exploring in my Deep Learning class. I could very easily distinguish the spectral features of a red-winged blackbird song from other birds’-as shown below- but having a computer do that posed to be a challenge. Now, I know that this type of pattern-recognition is well-suited for machine learning, though at the time I looked to the field that I had just begun studying: signal processing.

I explored different techniques I’ve found in signal processing literature and saw how well they applied to my problem (of course, with some suggestions from Rob). Among the things I tried were searching for recognizable signatures in the Fourier coefficients of the bird songs in the Fourier domain, a bang-bang control system to look for peaks at different heights, and manipulating the signals using tricks like convolution to make the song features more prominent.

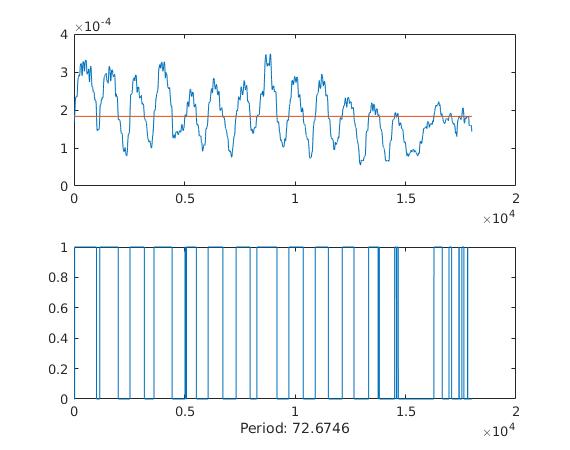

I ended up with three final products. First, I created a MATLAB GUI in which you can select the red-winged blackbird song from a short audio recording by selecting the area in the spectrogram that contains the red-winged blackbird song. The GUI then displays the song in the frequency domain, and the user can tune the parameters of the song, to maximize the prevalence of the song pattern. Once the user does this, the user receives the number of trills (oscillations) in the bird song, which I had determined to be the main distinguishing characteristic of red-winged black bird songs. In my final week of the project, my assumption was validated when I discovered a handful of ornithologist academic papers that empirisongy distinguished red-winged blackbird songs using the same method.

My second product was a MATLAB script which takes in a long audio file and the expected frequency of the song, and returns the time stamps where there might be red-winged blackbird audio songs. I only tested this program on two long (~18 minute) recordings, because I had to label my own testing data by listening to the audio recordings and marking the timestamps myself. Also, there isn’t a multitude of long audio recordings online where red-winged blackbird songs are prominently heard. On those two audio recordings however, my program worked on the two labeled audio files with 60 and 85% accuracy. The program worked by creating a sliding window in which each window is put through a peak detection algorithms which counts the number of oscillations in the segment.

My last result was testing my two programs on audio files from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. With the Cornell Lab’s files, I had access to red-winged blackbird files from all over the Americas. I used my programs and their data to see if I could quantify the regional dialects- which is something that is well known in the ornithologist community and which is easily recognizable on audio files of red-winged blackbirds of different regions. When I had set out to do this part of my project, I thought that this would be a great way to standardize and define bird dialects- and while I still believe that, during my last week I found that there has been some efforts in this space already, albeit the trill counting has been done by had. What I found was that there was no one frequency range that birds in a single region used to differentiate themselves. Instead, all the birds in one area sing in different frequencies to distinguish themselves from one another. Though it is still possible to hear the regional dialect that many birds in one region share, compared to birds of a different region. Therefore, more research is necessary to identify the parameters of that differentiation.

Looking back at my work for this project four years later, one of my main takeaways is that I now realize how closely I was working with machine learning topics and still not doing machine learning. If I were to do this project today, I would definitely try to apply some techniques from that space. Although I do think that there are cases where people throw machine learning at a problem that doesn’t warrant it, in this case I think it would be a good choice, because the task of recognizing and distinguishing bird songs is a pattern recognition problem for which more basic signal processing techniques didn’t suffice.

More information about this project can be found on my github repo.